Director: Adam McKay

Entertainment grade: B+

History grade: A–

The global economy went into recession from 2007-2009. One contributor to this was the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States.

Glamour: The Big Short begins in the 1970s with the invention of mortgage securities. In case you’re thinking of falling asleep or walking out, within three minutes there’s the line “The banker went from the country club to the strip club,” accompanied by footage of nearly naked ladies showing you their boobs and bums. It’s quite an annoying way to start, and may give the impression that the film will follow the lead of, say, The Wolf of Wall Street in trying to make the world of finance less tedious by submerging it in tits and glitter. There’s even a scene where Margot Robbie – who plays Jordan Belfort’s wife in The Wolf of Wall Street – explains the subprime mortgage securities market to camera while reclining in a bubble bath and drinking champagne. Fortunately, the film picks itself up from this point, and ends up being a good deal more thoughtful than this first act might lead you to believe.

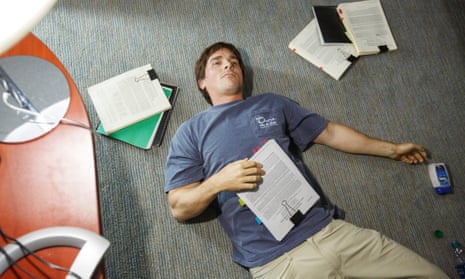

Characters: Michael Lewis’s The Big Short, the nonfiction book on which the film is based, was a bestseller when it came out in 2010. Lewis is one of the few people who can write about complicated finance or analytics and make it both comprehensible and gripping – as in his breakthrough book Liar’s Poker and his bestseller Moneyball (which was also adapted into a movie starring Brad Pitt). The Big Short’s screenplay is pretty faithful to Lewis’s book in its sharpness, wit and tone, and focuses on the same characters even though most have been semi-fictionalised and renamed. Michael Burry (Christian Bale) really was a stock market investor at Scion Capital; he wore no shoes and listened to thrash metal in the office. Mark Baum (Steve Carell) is based on hedge fund manager Steve Eisman; the movie keeps his Jewish background and straight talking. Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling) is based on Deutsche Bank bond salesman Greg Lippmann: “He wore his hair slicked back, in the manner of Gordon Gekko,” wrote Lewis, “and the sideburns long, in the fashion of an 1820s Romantic composer or a 1970s porn star.” The film’s Vennett sports disappointingly inadequate sideburns but has a penchant for the same braggadocio as Lippmann. Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt) is based on Ben Hockett, and has a similar apocalyptic outlook.

Markets: Quietly and separately, all these men spot that there is a problem with mortgage securities, particularly those resting on the unfettered inflation of the risky subprime market. The film is accurate about the historical trajectory of events. It is true that an astonishing number of people, including the chairman of the Federal Reserve himself, continued to ignore the housing market bubble and even to deny it could happen – though, as the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics Laureate Paul Krugman has pointed out in his review, more people noticed there was a problem than the tiny group who are shown here. Another economist, Jeffrey A Tucker, has argued that The Big Short is “incomplete” without reference to the actions of the Federal Reserve itself. He directs viewers looking for an accurate account of the causes of the crash to Margin Call.

The Big Short has a broader focus than Margin Call and a more explicitly political perspective. Historically speaking, though, its approach is equally valid: its focus is on the Wall Street personalities involved, the mind-blowing levels of denial and coverup among regulators, ratings agencies and banks, and ultimately the consequences. If its economics isn’t a full picture – well, there’s only so much you can say in two hours, and only so many celebrities the film-makers could entice into a bubble bath to explain things.

Veracity: Sometimes, The Big Short’s action stops and someone comments on the veracity of a scene. “Okay, this part isn’t totally accurate,” junior amateur investor Jamie Shipley admits as he and his colleague Charlie Geller (based on real investors Jamie Mai and Charlie Ledley) stumble across a document revealing the possible extent of the crisis. “We didn’t find the prospectus in a bank that rejected us. A friend told Charlie about it.” Historians rejoice! Divergence from the facts is acknowledged. Imagine if all films did this, though. Braveheart would be 12 hours long.

Morality: Everybody thinks the film’s protagonists have gone bananas, but in 2007 the mortgage market begins to wobble just like they said it would. Things get really bad, though, with the collapse of the bank Bear Stearns in 2008. Bear Stearns, indeed. Did no one notice that its name was practically a synonym for Uncovered Arses? Yet The Big Short does not gloat as the banks topple. Instead, it gets angry. Each of its ensemble cast members – with the exception of the reptilian Vennett – is gutted by being proved right. Though they may all be able to cry themselves to sleep on a gigantic pile of money, the terrific performances (especially from Carell and Bale) make this genuinely striking. “I have a feeling that in a few years people will be blaming immigrants and poor people,” sighs Baum. It’s easy to be prophetic when you’re making a film a few years after the events. Still, the scene in which Baum’s colleagues are on the steps of St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, watching people go by and wondering sadly how many of them are going to lose their livelihoods, is authentic.

Verdict: Fast, funny and righteously furious, The Big Short is more gripping and less desperate to make jerks in suits seem cool than most business movies. It’s also a solid historical explanation of the subprime crisis.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion